Today is the 78th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki. While in part 1 I discussed how the horrors of war made the decision to drop the bomb easier, ultimately, ends should not justify means when it comes to making moral decisions. Since the dropping of the atomic bombs in 1945, the Church has spoken out against the use of nuclear weapons and worked for disarmament around the world.

St. John XXIII helped to deescalate the Cuban missile crisis. In his 1963 encyclical Pacem in Terris, he urged for a nuclear weapons ban and disarmament agreement. The Limited Test Ban Treaty was concluded four months later.

St. John XXIII writes, “There is a common belief that under modern

conditions peace cannot be assured except on the basis of an equal balance of

armaments and that this factor is the probable cause of this stockpiling of

armaments….if one country is equipped with atomic weapons, others consider

themselves justified in producing such weapons themselves, equal in destructive

force.”

He acknowledged the challenge of disarmament goes beyond treaties and bans but requires a moral, spiritual commitment to peace—a goal often preached and never realized. He says, “Unless this process of disarmament be thoroughgoing and complete, and reach men's very souls, it is impossible to stop the arms race, or to reduce armaments, or—and this is the main thing—ultimately to abolish them entirely. Everyone must sincerely co-operate in the effort to banish fear and the anxious expectation of war from men's minds.”

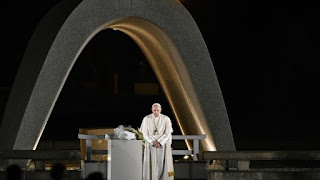

Pope Francis decried the use of nuclear weapons in his 2019 trip Hiroshima. He said, “Here, in an incandescent burst of lightning and fire, so many men and women, so many dreams and hopes, disappeared, leaving behind only shadows and silence. In barely an instant, everything was devoured by a black hole of destruction and death. From that abyss of silence, we continue even today to hear the cries of those who are no longer….I felt a duty to come here as a pilgrim of peace, to stand in silent prayer, to recall the innocent victims of such violence, and to bear in my heart the prayers and yearnings of the men and women of our time, especially the young, who long for peace, who work for peace and who sacrifice themselves for peace.”

“When we yield to the logic of arms and distance

ourselves from the practice of dialogue, we forget to our detriment that, even

before causing victims and ruination, weapons can create nightmares; ‘they call

for enormous expenses, interrupt projects of solidarity and of useful labour,

and warp the outlook of nations’ (quoting St. Paul VI’s 1965 address

to the UN). How can we propose peace if we constantly invoke the threat of

nuclear war as a legitimate recourse for the resolution of conflicts? May

the abyss of pain endured here remind us of boundaries that must never be

crossed. A true peace can only be an unarmed peace.”

The Church’s stance continues to be disarmament, though she

recognizes the hurdles of reaching such a goal. The Secretary of the Dicastery

on Integral Human Development recently said, “There is no illusion that the

number of weapons will disappear as if by magic or after moral and legal

condemnation. Therefore, the Holy See is equally engaged in a step-by-step

dialogue with nuclear-armed states whose commitment remains crucial to the

achievement of any serious and realistic discussion of nuclear arms control.”

Peace is an ongoing, conscious work, not merely the absence of war. Using weapons as deterrents is still using weapons and a threat of violence. Christians are called to advocate for true peace, one where swords are turned into plowshares. Despite the quagmire of diplomacy, the goalposts cannot be moved, inching us closer to justifying violent actions, especially ones as destructive as nuclear weapons.

In his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritae, Pope

Benedict XVI says, “Human freedom can make its intelligent contribution to

positive evolution, but it can also add new evils, new causes of suffering, and

real setbacks. For this reason, the Church’s action not only seeks to recall

the duty to care for nature, but at the same time ‘must above all protect

mankind from self-destruction.’”

We cannot put the genie back in the bottle. What we do with

our nuclear knowledge is something humanity will always have to continue to

debate. Hopefully, together, our knowledge and any scientific advancement can

be used for good. God created and gave us domination over the creation; it is

our duty to be good stewards.

No comments:

Post a Comment